A personal testimony about the impact of Cabrel's music, from an African childhood to today.

I was twelve years old, with a Walkman in my pocket and half-full Tudor batteries. It was a time when music invited itself into the tumult of travels, into the noise of markets, into the chance encounters of sound. I was a student at Notre-Dame du Lac, in Togoville, on the shores of Lake Togo.

To return to Benin, the journey was almost ritual: first crossing the lake by pirogue, with all the risks that entailed. Then walking for long minutes along a discreet path bordered by bushes to reach the interstate road. From there, taking a taxi that passed through Kpémé and Aného. After crossing the Togo-Benin border on foot, we finally entered Hilla-Condji, the beating heart of an open-air market, where famous cassette stalls broadcast music at full volume.

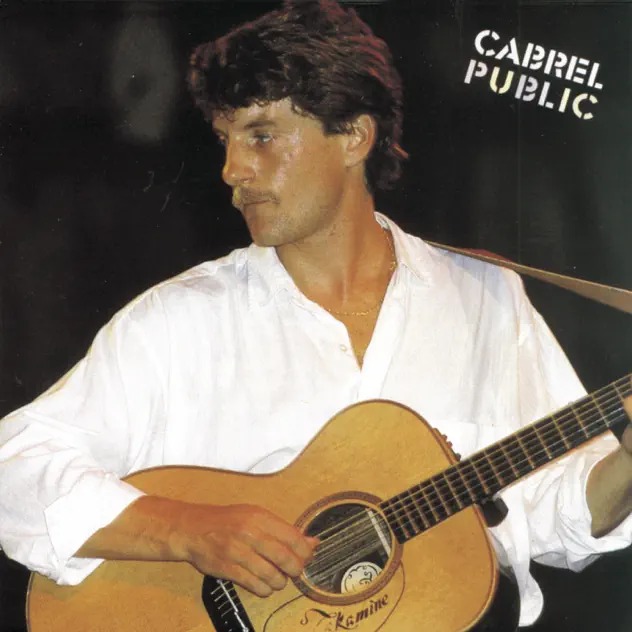

That's where I heard "Carte Postale." Cabrel was singing. And that day, without knowing it, I began a lifelong companionship.

A voice found before ever knowing it

This moment was a revelation. This song spoke to me like few others. My already music-loving ears had managed to isolate, among a dozen songs booming simultaneously, the one that stopped me in my tracks. I took pleasure in listening to it until the end before crossing the street to buy the cassette.

From that day on, Cabrel became more than an artist to me: a brotherly voice that accompanied me from adolescence to maturity. It was also the era of using pens to rewind tapes to save batteries, and finally the half-pleasure of listening to a song that had slowed down due to lack of energy. But what pleasure nonetheless!

From radio host to fifty-year-old - an unwavering loyalty

In 1998, I had the chance to become a radio host - for a year at the Office of Broadcasting and Television of Benin (ORTB). My sign-off shows, broadcast between 11 PM and midnight, often ended with a Cabrel song. Nothing better to close a day than his deep voice, his carefully chosen words, and that impression that the world could still be a little gentler before night fell.

His songs followed me through my studies, my friendships, my questions. Cabrel was part of the household. I listened to him in the car, at the office, while traveling, as well as in my moments of silence.

I've known all the stages: cassettes that needed to be rewound with a pen to save batteries, CDs that we carefully slipped into their cases, MP3 files that we exchanged like treasures, and today streaming, which allows me to carry his entire repertoire in my pocket.

Even today, at 50 years old, each song appears to me like an old friend who knows my secrets.

Discovering the man behind the music

In a profound interview on "Clique", I discovered a man of great modesty. Cabrel doesn't chase after fame, as he explains himself:

"The light is on my songs. As for me, I've always hidden a bit."

He speaks with humility about his work, his working-class childhood, and slowness as a strength. He defines himself as a "happy country bumpkin," a proud countryman. This relationship with rurality, far from the tumult of cities, resonates deeply with me.

A craftsman rather than a poet

What struck me in the interview was his way of talking about his creative process. Far from the image of a poet, he sees himself more as a craftsman:

"I have a facility for daydreaming, for imagination a bit, but well, what do you do with that? Sometimes nothing at all. So I said to myself: look, I'm going to talk to others since I couldn't address them directly, through songs. And it's true that I worked a lot, a lot."

This vision of work, this daily persistence to refine his texts and melodies, perfectly illustrates what his songs have represented in my own life: a faithful companionship, a constant presence that required not flashes of genius, but a daily faithfulness.

An intimate and universal work

Cabrel writes songs like one makes a film: from the very first line, everything is there. He says it himself: "My great obsession is that everything must be almost already said in the first line. We don't have time to waste in songs."

His texts speak of love, loss, fatherhood, justice. His songs are miniatures loaded with soul, short films in three minutes. Among those that have marked me the most:

- "La Corrida": the bull speaks, giving a voice to those who have none.

- "Je t'aimais, je t'aime, je t'aimerai": a declaration both simple and overwhelming, written as he recounts "during a 4-hour train journey."

- "Les Tours Gratuits": the emotion of a father facing his daughters' departure, the echo of carousels now empty.

- "L'encre de tes yeux": a song that begins with "Since we'll never live together," immediately placing the listener in a situation of impossible love.

The relationship with time

What also touches me about Cabrel is his relationship with time, this slowness embraced in an increasingly fast-paced world. When asked what wealth means to him, he answers:

"My greatest luxury has been having time. That means taking time to arrive and to work, as we always come back to this idea of the craftsman at his workbench."

This vision resonates particularly today, as I often find myself seeking spaces of slowness in an increasingly accelerated daily life.

And where do I fit in all this?

I am that twelve-year-old boy who never stopped listening. And today, I am that fifty-year-old who remembers. Cabrel has crossed through my life without ever forcing the door.

"No need for phrases, nor long speeches."

His music remains for me a space of reverie, a refuge against the noise of the world. As he himself says in the interview: "Songs are made to make you dream, to reassure. They have a beautiful mission, I think. They also embellish the everyday."

So simply: thank you, Francis. For the songs, for the loyalty, for the modesty. For having been, since that day in Hilla-Condji, my traveling companion.