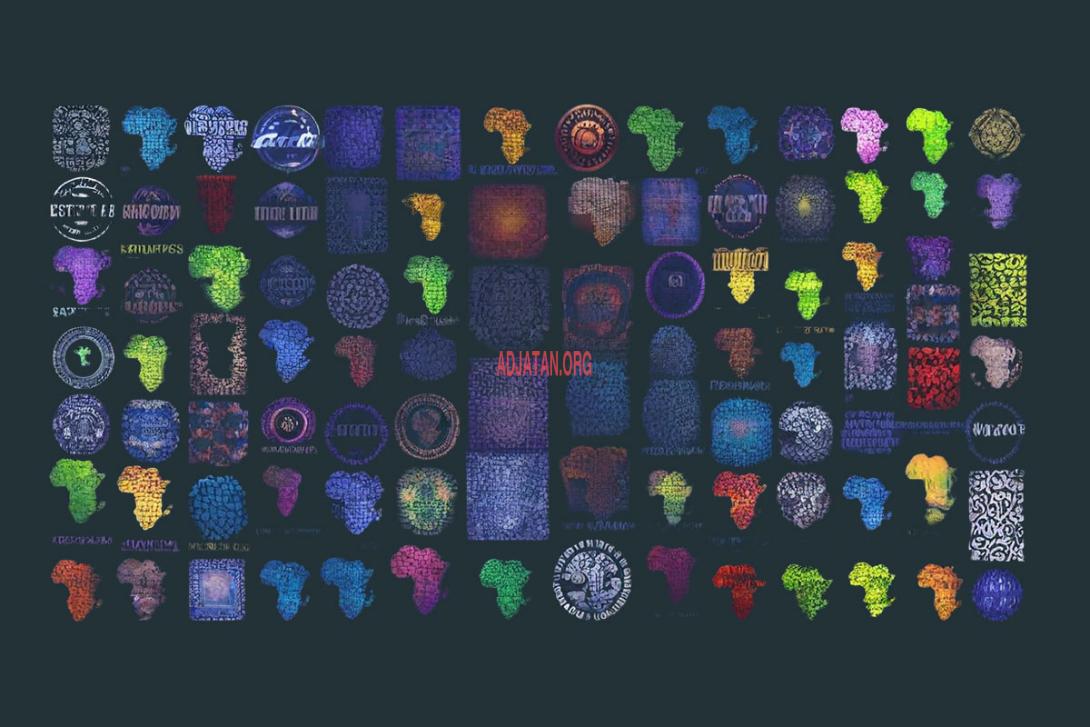

In the realm of visual symbols that instantly communicate complex ideas, few shapes are as recognizable or as deeply freighted with meaning as the silhouette of the African continent. This distinctive geographical form—with its pointed southern tip, rounded western bulge, and northeastern horn—has transcended mere cartographic representation to become a powerful icon in global visual culture. From the emblems of pan-African political movements to the logos of international NGOs, from album covers to fashion statements, Africa's outline serves as shorthand for an entire constellation of ideas, aspirations, and identities.

What makes this phenomenon particularly striking is its singularity. While other continental shapes occasionally appear in branding and visual culture, none do so with the frequency or symbolic weight of Africa. Unlike other continents whose forms proceed from complex assemblages and whose limits can be fuzzy, the fact that Africa is immediately perceived in its graphic totality, as a uniform mass, has contributed to both its iconic power and, at times, to reductive conceptions. This observation raises profound questions about why this particular geographical form has acquired such prominence, and what this tells us about both historical power relations and contemporary identity formation.

The Pictographic Power of Africa's Form

The answer begins, perhaps, with pure visual distinctiveness. Africa's silhouette possesses what designers would call high "memorability" and "reproducibility"—qualities essential to effective logo design. Its form is compact, bounded by seas on nearly all sides, and features recognizable protrusions and indentations that make it difficult to confuse with any other landmass.

This visual quality was notably observed by Congolese artist Albert Mongita in 1964, when creating an illustration for the First World Festival of Negro Arts held in Dakar in 1966.

"Africa adopts the form of a human figure, symbol of its total unity."

This anthropomorphic interpretation went further, as Mongita divided the continent into three symbolic parts: the head representing the northern countries (the "Brain" of Africa), the eyes and nose symbolizing the central countries that "see and smell dangers," and the mouth and chin representing the southern countries, with South Africa specifically portrayed as a closed mouth refusing to speak—a powerful political statement about apartheid-era South Africa's isolation from the rest of the continent. In Mongita's interpretation, Madagascar was symbolized by an earring attached to Africa by a bead, suggesting its integral connection to the continent.

Unlike Eurasia, with its contested continental dividing line, or the Americas, which stretch across hemispheres, Africa presents itself as a coherent visual unit. This geographical coherence has made it particularly suitable for adoption as a symbol, especially in contexts where unity and shared identity are being emphasized. The continent's shape seems to naturally embody what many movements have sought to articulate: that despite internal diversity and the arbitrary nature of colonial borders, there exists a fundamental wholeness to Africa as a concept.

Within this form, three prominences stand out: to the west a bump, like a femoral head; to the east a rhinoceros horn or sword point stretched out; and to the south a long drop ready to drip. These organic, almost living qualities of the shape contribute to its symbolic power—it doesn't just represent a landmass but suggests something alive, dynamic, and unified.

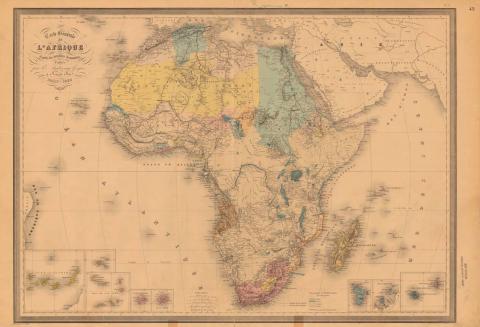

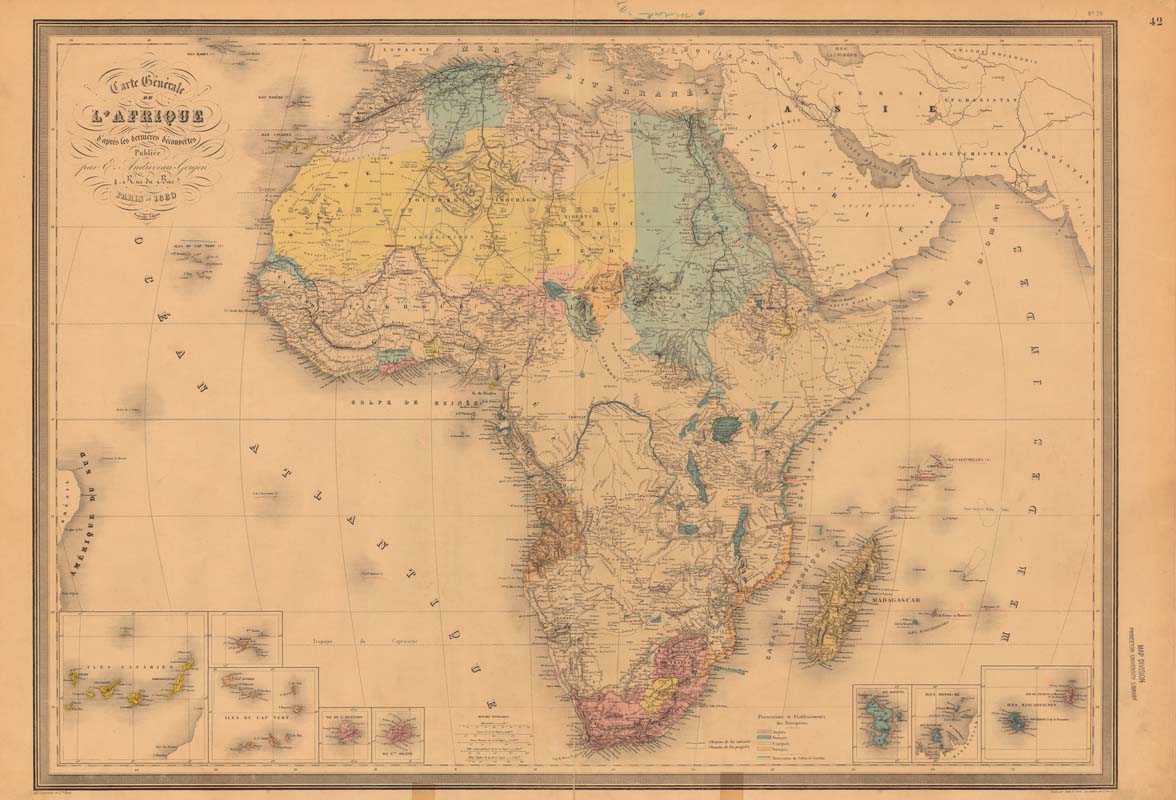

Historical Roots of Continental Symbolism

The use of Africa's outline as an emblem has deep historical roots, though its contemporary prominence emerged largely in the context of 20th-century independence movements and pan-Africanism. The map of the contours of Africa has become the sign of a community of destiny of enslaved, dominated and brutally treated peoples. This transformation of geographical form into resistance symbol highlights how cartography, typically a colonial tool for division and control, was reclaimed and repurposed.

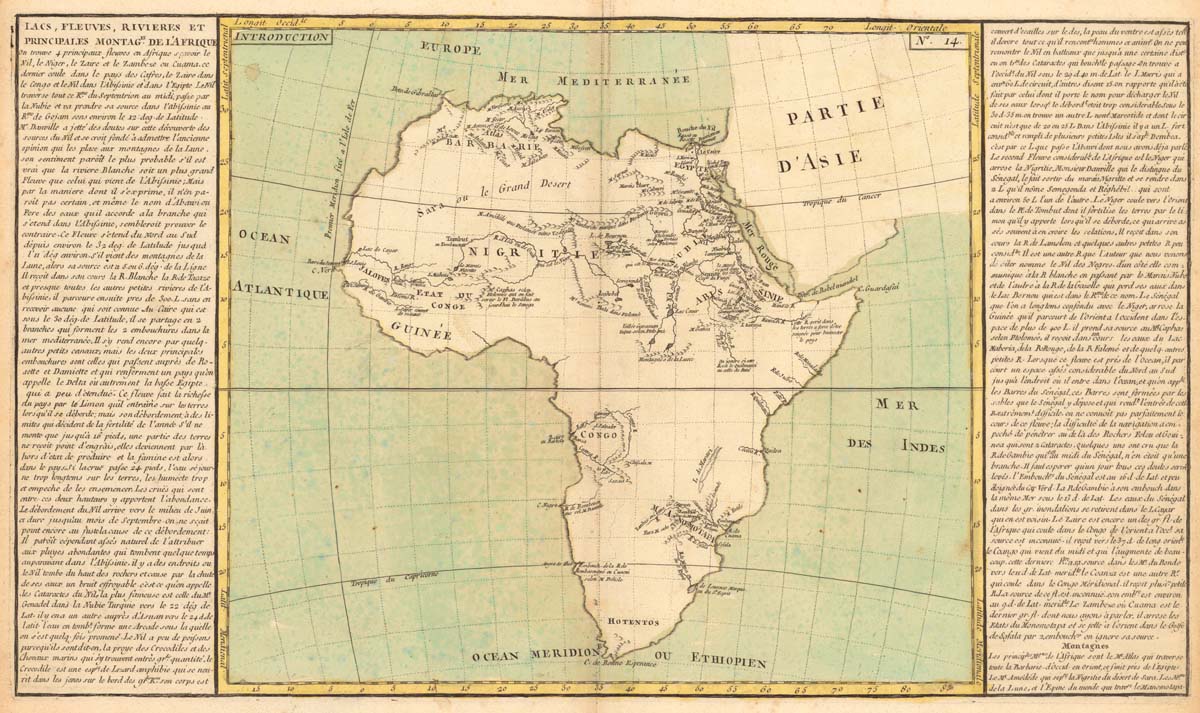

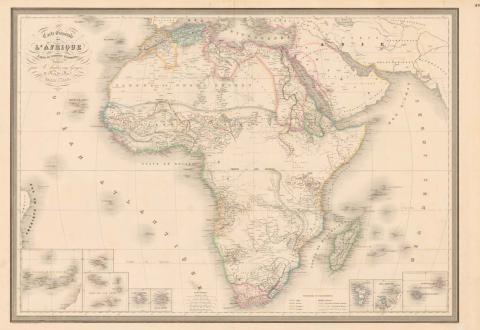

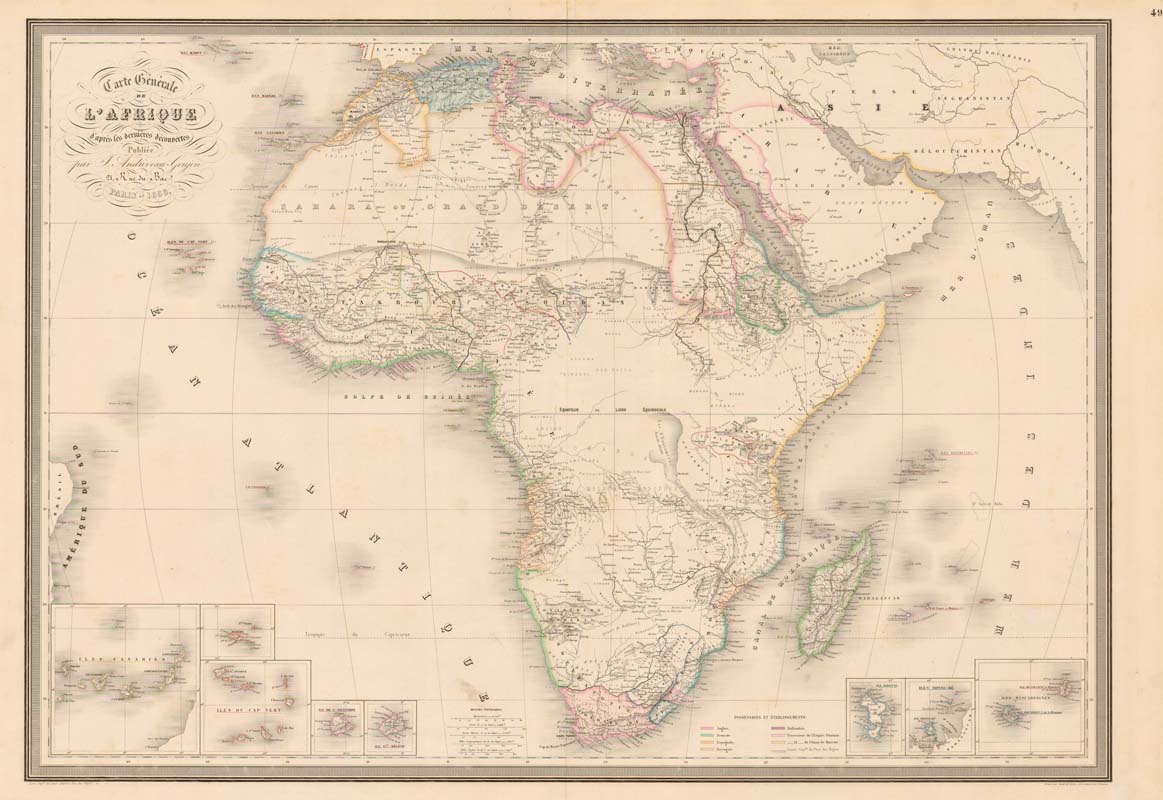

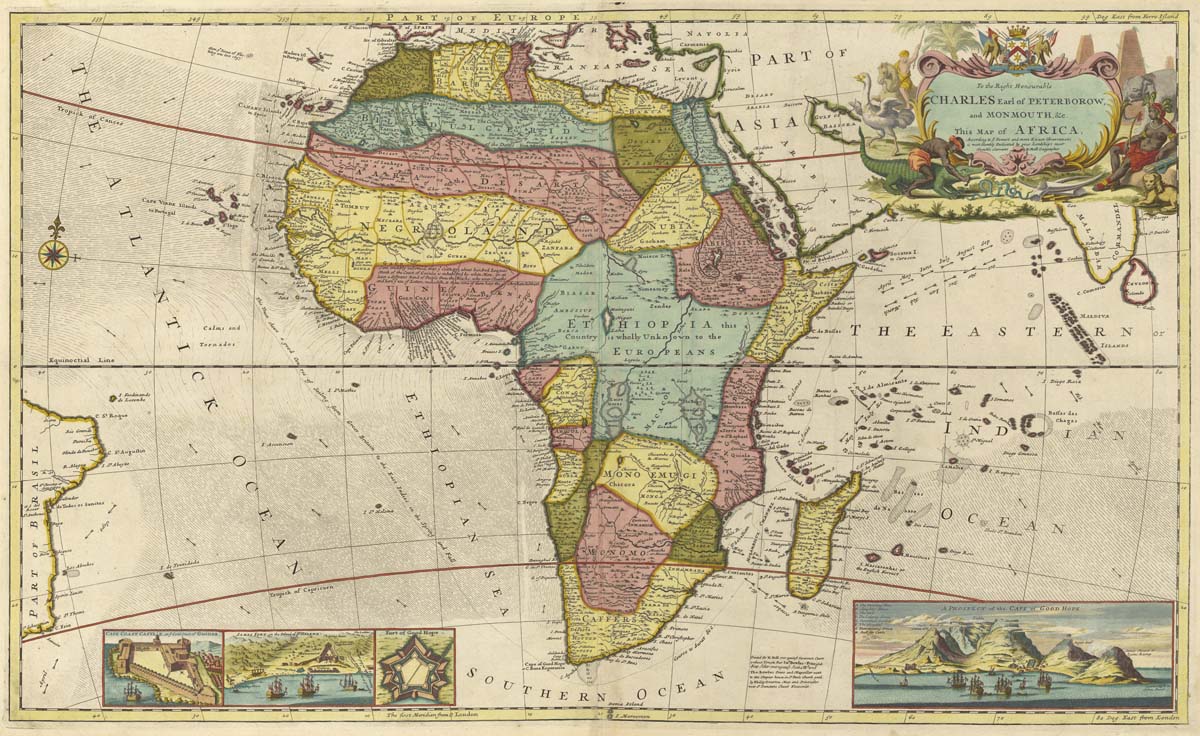

This reclamation emerged from a specific historical context. European colonial powers had, at the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference, carved up the continent with territories delimited on maps that colonial powers considered "virgin"—that is, empty of institutions capable of resisting their projects. These arbitrary divisions, which often ignored existing cultural and political boundaries, would later become the borders of independent African nations.

In a profound irony, the very cartographic representation that facilitated colonization became a unifying symbol against it. The continent's outline—which colonial powers had carefully mapped to divide and rule—was reclaimed as an assertion of shared identity and common cause. Organizations like the Organization of African Unity (later the African Union) adopted the continental silhouette as a visual assertion that African unity transcended the artificial divisions imposed by European powers.

The symbolism here is potent: what was once a European cartographic construction—the continent as a neatly bounded entity—became a symbol of pan-African resistance and solidarity. The outline that European mapmakers had drawn to facilitate colonial administration was repurposed as a visual assertion of African self-determination and unity.

Contemporary Branding and Visual Identity

Today, the African outline appears in countless logos and visual identities, serving multiple symbolic purposes. For pan-African political organizations and African multinational corporations, it communicates continental scope and ambition. For development NGOs and humanitarian organizations, it efficiently identifies their geographical focus. For cultural institutions and movements, it signals an engagement with African heritage and identity.

This prevalence stands in stark contrast to other continents. European organizations rarely use Europe's outline as their primary visual identifier, nor do Asian entities typically employ Asia's shape. North and South American outlines appear occasionally but nowhere near as frequently as Africa's. Australia presents the closest parallel—another continent with a distinctive, island-like silhouette that appears in national and commercial branding—but even this usage pales in comparison.

Why this disparity? One explanation lies in the more or less congruent "inventions" that have shaped perceptions of Africa. The continental outline became a convenient visual container for these invented conceptions—both negative stereotypes imposed from outside and positive identities asserted from within. The simplified vision of the continent as a cartographic unit became a background of the widely shared and undiscussed imaginary, which notably served as a chassis for reductive conceptions concerning Africa as an undifferentiated totality.

It goes differently for the other continents because their forms are more complex assemblages with sometimes fuzzy limits. Europe and Asia form a vast agglomeration with peninsular protrusions, but no clear physical boundary marks where Occident ends and Orient begins. The Americas stretch across two large masses connected by a fragile central tegument. Oceania gathers discontinuous insular confetti around Australia. This uniqueness of Africa's visual coherence partly explains why its outline has become such a widespread and powerful symbol.

The Emotional Charge of Geographic Form

Beyond the practical aspects of visual distinctiveness and historical context lies a deeper psychological dimension. Geographic shapes can carry profound emotional significance, particularly for peoples who have experienced colonial occupation, territorial loss, or diaspora. The continental outline serves as what sociologists might call a "symbolic boundary marker"—a visual affirmation of belonging and identity.

This emotional dimension helps explain why the African silhouette appears not just in formal logos but across cultural expressions. From jewelry to textiles, from street art to academic book covers, the continent's shape serves as a pictogram—a visual shorthand that condenses complex meanings into an instantly recognizable form.

For communities in the African diaspora—particularly those descended from people forcibly removed through the transatlantic slave trade—the continental outline can serve as a poignant symbol of ancestral homeland and cultural reconnection. This explains its frequent appearance in Afrocentric art, fashion, and cultural products, where it functions as a visual assertion of heritage and belonging.

The emotional power of this symbolism was particularly evident in the Black Power and Pan-African movements of the 1960s and 1970s, when the continental silhouette became a prominent visual element in everything from political posters to album covers. Artists incorporated the African outline into their visual aesthetic as part of a broader exploration of Black identity and reclaimed heritage. These usages helped cement the continent's shape as not just a geographical representation but a charged cultural signifier.

The continent's shape seems to naturally embody what many movements have sought to articulate: that despite internal diversity and the arbitrary nature of colonial borders, there exists a fundamental wholeness to Africa as a concept.

Colonial Cartography and Visual Reclamation

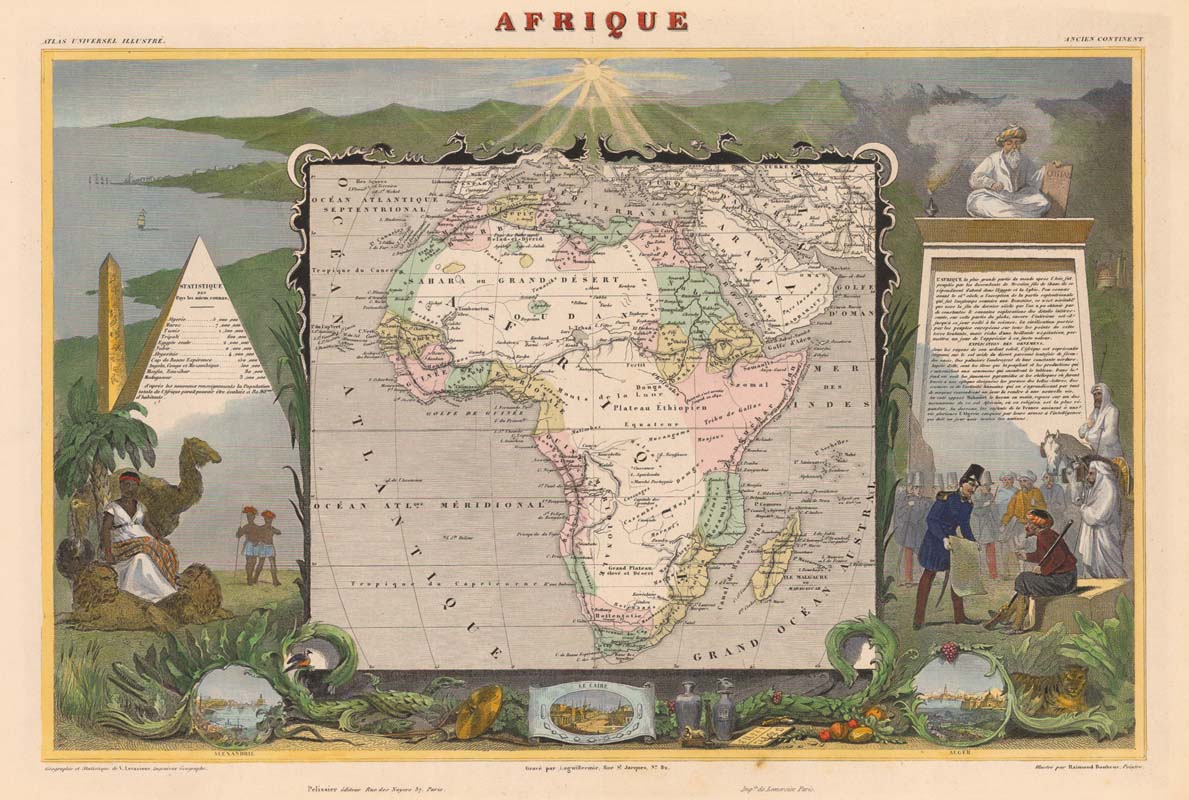

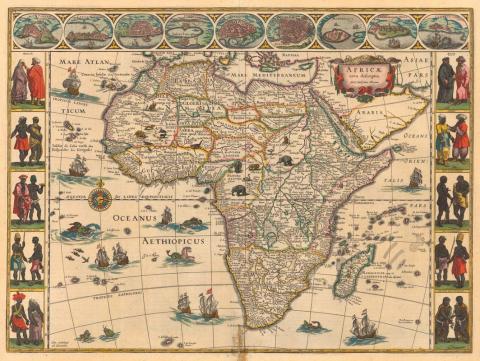

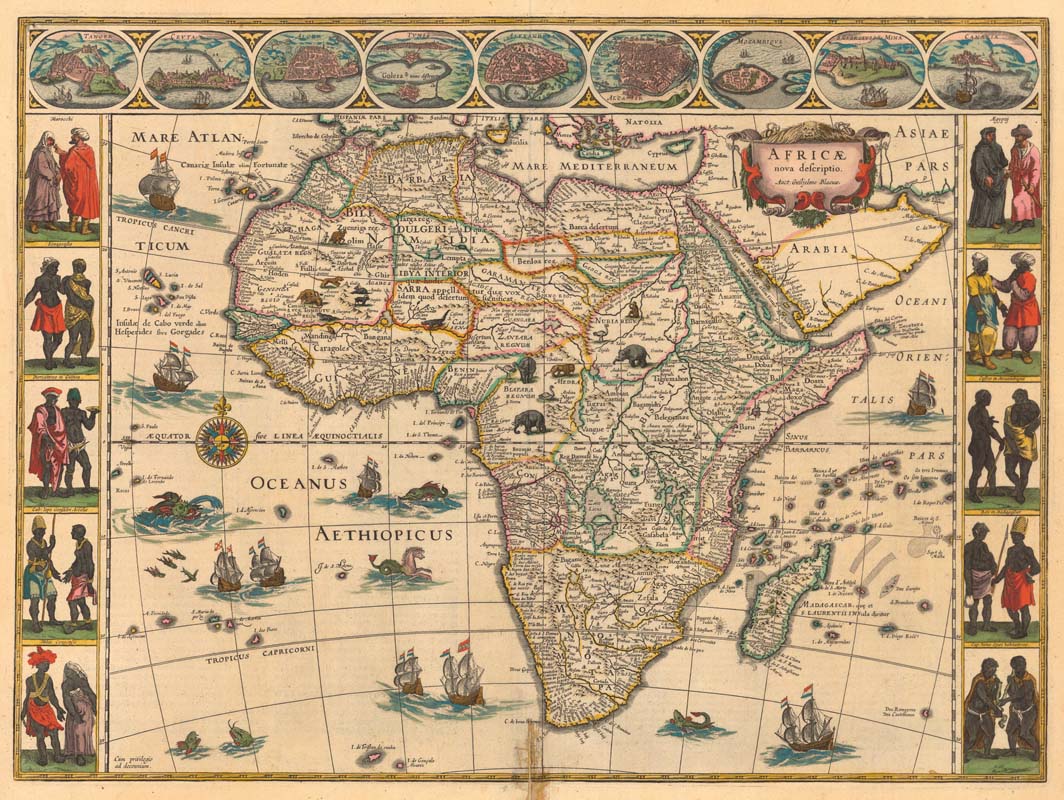

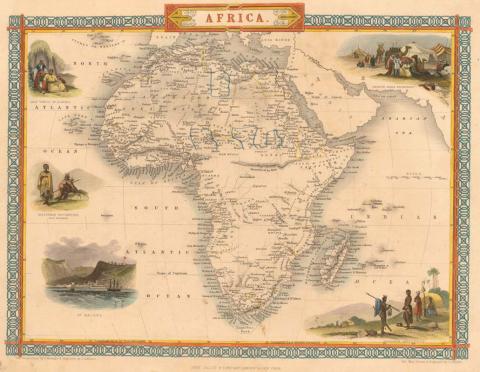

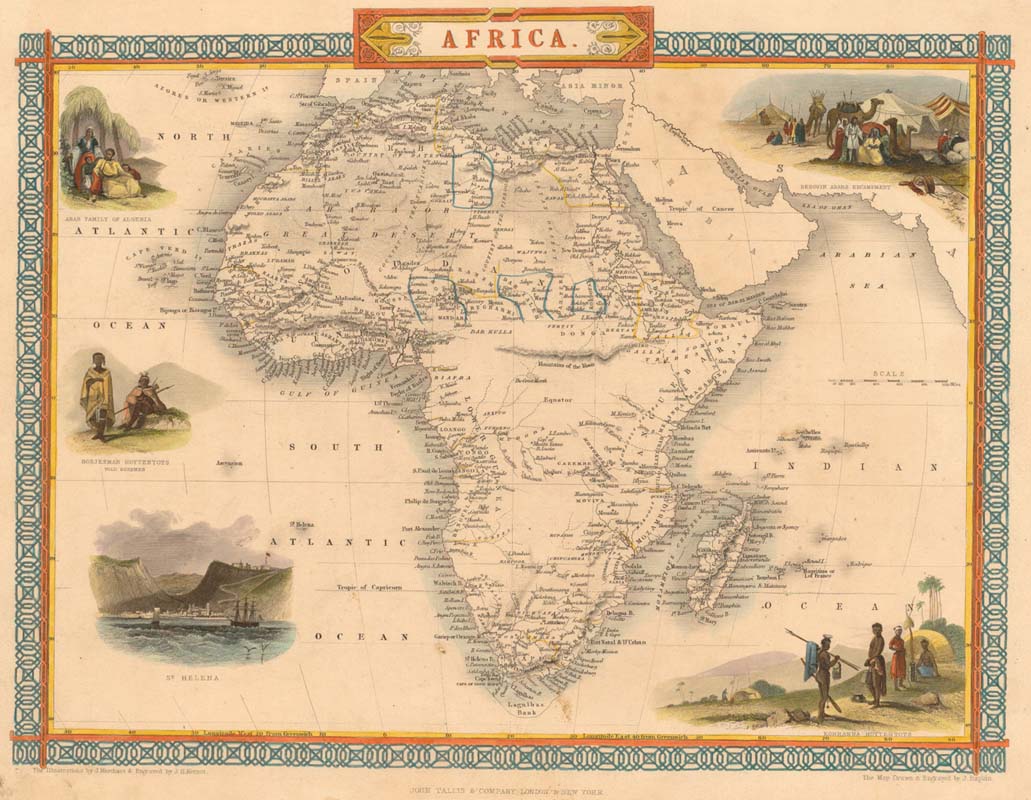

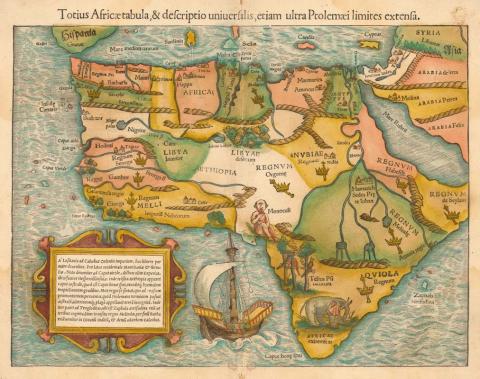

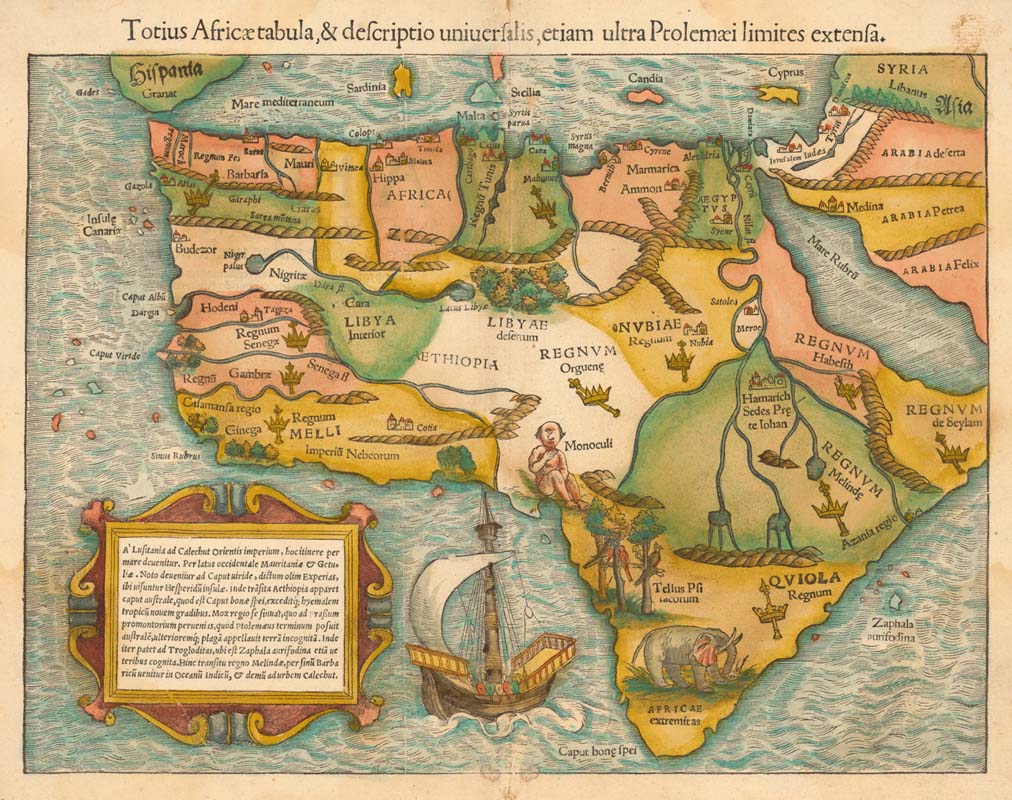

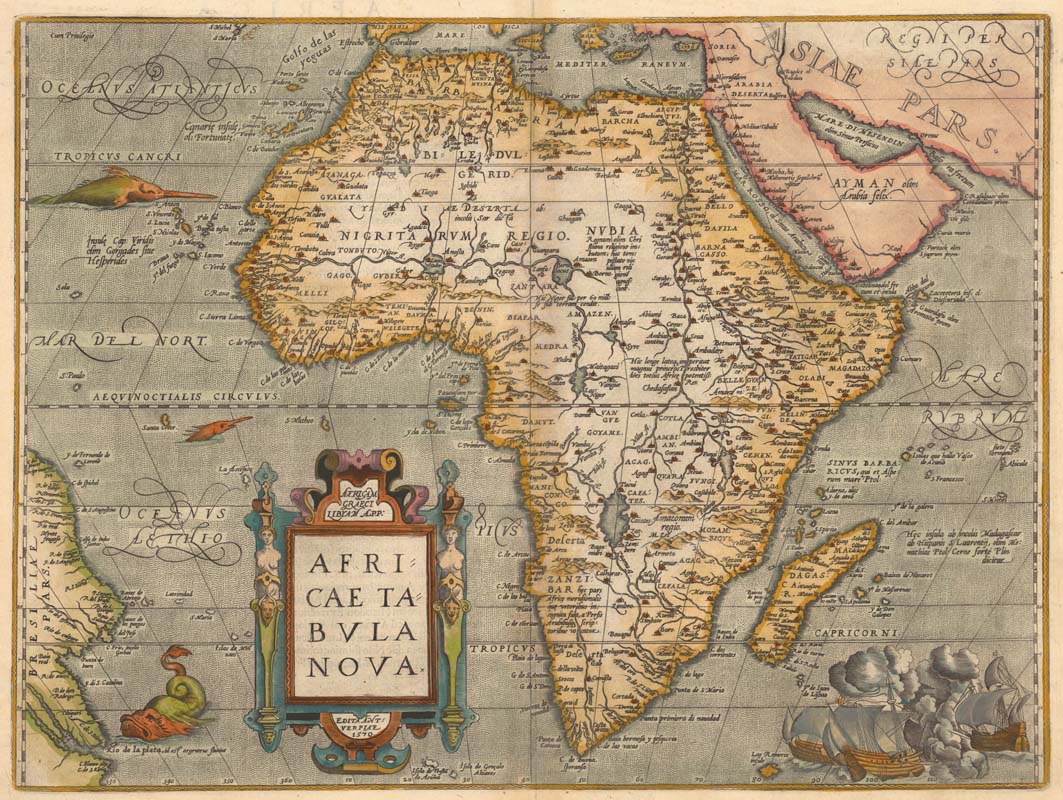

The relationship between colonial cartography and Africa's modern visual representation is complex and multifaceted. European explorations of Africa's coastlines in the 15th and 16th centuries marked a pivotal moment in how the continent was visually represented. It was on the surface of an Africa still poorly mapped, in the course of exploration, that European powers considered virgin—that is to say empty of institutions and social forces capable of countering their projects—that they cut out a vast puzzle.

Early European maps of Africa's interior often filled unknown spaces with mythical elements and drawings of supposed inhabitants. As the English poet Jonathan Swift famously satirized:

"On maps of Africa, geographers fill the blanks with images of savages and on uninhabitable hills, they place elephants for want of towns."

Later, in the 18th century, these imaginative fillings were replaced by blank spaces, creating the image of Africa as an "empty envelope" awaiting European documentation and control.

This cartographic emptying was not innocent; it facilitated a colonial imagination that positioned Africa as a space awaiting European intervention and ordering. The continent's outline became the container for this project—a clearly defined edge within which European powers could project their ambitions and fears.

The modern reclamation of Africa's shape as a symbol of pride and unity must be understood against this historical backdrop. When contemporary African organizations and movements adopt the continental outline, they are not simply using a convenient visual form but participating in a profound act of symbolic reclamation.

Transcending historical vicissitudes and offering a single profile, the contours of Africa have constituted a cartographic object that lends itself to multiple uses. The African silhouette can be worn as jewelry or printed on clothing, can serve as the basis for logos of international organizations, import-export companies, or charitable works, and can suffice on an album cover to suggest entry into rhythmic and vibrant musical territories.

They are taking a shape that once facilitated colonization and repurposing it as an assertion of self-definition and continental solidarity.

As if to conjure these threats of dislocation, the map of the contours of Africa—Africa as a pictogram—has become the sign of a community of destiny of enslaved, dominated and brutally treated peoples. This reclamation has visual precedents across other formerly colonized regions. Indigenous peoples in the Americas have similarly reclaimed pre-colonial maps and territorial representations as assertions of sovereignty and cultural continuity. However, the African case stands out for the centrality of the continental outline itself, rather than specific regional territories, in these visual politics of reclamation.

Transcending historical vicissitudes and offering a single profile, the contours of Africa have constituted a cartographic object that lends itself to multiple uses. The African silhouette can be worn as jewelry or printed on clothing, can serve as the basis for logos of international organizations, import-export companies, or charitable works, and can suffice on an album cover to suggest entry into rhythmic and vibrant musical territories.